1. Executive Introduction: The Unraveling of a Legacy

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is currently navigating one of the most precarious periods in its operational history following the catastrophic failure of the PSLV-C62 mission on January 12, 2026. This incident, which resulted in the loss of the strategic Earth Observation Satellite EOS-N1 (codenamed "Anvesha") and fifteen co-passenger payloads, was not an isolated anomaly but rather a chilling echo of the PSLV-C61 failure that occurred merely eight months prior in May 2025. Both missions were terminated by a malfunction in the third stage (PS3) of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), a rocket that has served as the backbone of India's space ambitions for over three decades.

For a launch vehicle that had cultivated a global reputation for reliability - boasting a success rate exceeding 95% and carrying out complex missions such as Chandrayaan-1 and the Mars Orbiter Mission - this sudden regression into serial failure represents a profound crisis. The consecutive nature of these failures, both localized to the solid-propellant third stage and manifesting with nearly identical telemetry signatures (drop in chamber pressure and roll rate disturbances), points toward a systemic pathology within the manufacturing, quality assurance, or design verification processes of the propulsion systems.

The stakes of these failures extend far beyond the immediate loss of hardware. Strategically, India has lost two critical "eyes in the sky" within a single year: the radar-imaging EOS-09 and the hyperspectral EOS-N1. This creates a significant gap in national security surveillance capabilities at a time of heightened geopolitical sensitivity along the borders. Commercially, the failures strike at the heart of NewSpace India Limited (NSIL), ISRO’s commercial arm, which is aggressively positioning the PSLV as a preferred carrier for the global small satellite market. The loss of payloads from international customers in the UK, Spain, Brazil, and Nepal, alongside domestic innovations from startups like Dhruva Space and OrbitAID, threatens to erode the trust capital that ISRO has built over decades.

This report provides a comprehensive, expert-level reconstruction of the crisis. It delves into the granular technical details of solid rocket motor ballistics to understand the failure mechanism, analyzes the strategic void created by the loss of the EOS satellites, evaluates the economic repercussions for the burgeoning Indian space ecosystem, and scrutinizes the institutional opacity regarding the C61 investigation that may have contributed to the C62 disaster.

2. The Architecture of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV)

To understand the specific nature of the failure, it is essential to first establish the engineering baseline of the PSLV. It is a four-stage expendable launch vehicle that employs a unique mix of solid and liquid propulsion stages, alternating between the two technologies to optimize lift-off thrust and orbital insertion precision.

2.1 The Propulsion Stack

The vehicle stands approximately 44 meters tall and serves as India's primary medium-lift launcher. Its architecture is defined by the following stages:

PS1 (First Stage): One of the largest solid rocket boosters in the world, the S139 motor carries 138 tonnes of Hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene (HTPB) propellant. It is augmented by strap-on motors (PSOMs), the number of which varies depending on the mission configuration (Generic, CA, XL, or DL).

PS2 (Second Stage): A liquid-fueled stage powered by the Vikas engine, a derivative of the French Viking engine. It burns UDMH (Unsymmetrical Dimethylhydrazine) and Nitrogen Tetroxide (N2O4) to provide sustained thrust during the atmospheric exit phase.

PS3 (Third Stage): The focal point of the recent failures, this is a solid rocket motor designated as the S-7. It carries approximately 7,600 kg of HTPB-based solid propellant and is designed to provide the high-velocity kick required to push the payload stack towards orbital velocity after the vehicle has escaped the dense atmosphere.

PS4 (Fourth Stage): The terminal stage, powered by twin liquid engines using Monomethyl hydrazine (MMH) and Mixed Oxides of Nitrogen (MON). This stage is restart able and provides the precise velocity trims and attitude control needed for accurate orbital injection.

2.2 The PS3 Solid Motor: Design and Vulnerabilities

The third stage, or PS3, is a critical component of the launch profile. Unlike liquid engines, which can be throttled or shut down in the event of an anomaly, a solid rocket motor (SRM) is essentially a controlled explosion. Once ignited, it burns until the propellant is exhausted.

Motor Case: The S-7 motor case is typically constructed from high-strength composite materials (filament-wound Kevlar or carbon epoxy) to minimize inert mass while containing high internal pressures (typically 4-6 MPa).

Propellant Grain: The HTPB propellant is cast into a specific geometric configuration (grain) to tailor the thrust profile. The burning surface area determines the mass flow rate and, consequently, the thrust.

Thrust Vector Control (TVC): Since the solid motor cannot be throttled, steering is achieved via a flex nozzle system. The nozzle is submerged into the motor case and can be gimbaled to vector the thrust for pitch and yaw control. Roll control during the PS3 burn is typically managed by the Reaction Control System (RCS) of the subsequent PS4 stage, as single-nozzle solid motors cannot generate rolling torque control.

The reliance on a solid third stage places immense pressure on manufacturing quality. Any defect in the propellant casting (voids, cracks) or the bonding between the propellant and the case (debonding) can lead to catastrophic failure modes such as burn-through or over-pressurization, which are unrecoverable in flight.

3. The Precursor: Anatomy of the PSLV-C61 Failure (May 2025)

The trajectory toward the January 2026 disaster began eight months earlier with the PSLV-C61 mission. Understanding this event is crucial, as it established the pattern of failure that would be repeated with PSLV-C62.

3.1 Mission Profile and Anomaly

On May 18, 2025, the PSLV-C61 launched from Sriharikota carrying the EOS-09 radar imaging satellite. The mission proceeded nominally through the first and second stages. The separation of the PS2 stage and the ignition of the PS3 stage occurred as planned. However, telemetry soon indicated a deviation.

ISRO Chairman S. Somanath (referred to as V. Narayanan in press reports) later confirmed that the mission failed due to a "fall in chamber pressure" of the third-stage motor. Without sufficient pressure, the motor could not generate the required thrust to achieve the necessary velocity increment (Delta V). The vehicle, unable to sustain its trajectory, fell short of the orbital velocity and re-entered the atmosphere, destroying the EOS-09 payload.

3.2 The Investigation and Opacity

Following the C61 failure, ISRO constituted a Failure Analysis Committee (FAC) to investigate the root cause. However, in a break from the agency's traditional transparency, the FAC report was not released to the public. It was submitted to the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) in August 2025, but the specific technical findings remained classified.

The agency announced a "return to flight" within months, citing "structural reinforcements" as the corrective measure. This vagueness raised concerns among industry observers. If the root cause was a propellant defect or a nozzle erosion issue, structural reinforcements to the casing might not address the underlying pathology. The decision to keep the report internal prevented external peer review or scrutiny of the "Return to Flight" (RTF) criteria, setting the stage for the subsequent failure.

3.3 The Ghost in the Machine

The C61 failure was the first indication that something was amiss with the S-7 solid motor production line. Solid motors are produced in batches. If C61 suffered from a "bad batch" of raw materials (e.g., substandard HTPB binder or defective curing agents) or a flaw in the curing process, it was statistically probable that other motors from the same production run would harbor similar latent defects. The failure to publicize the root cause suggests that ISRO may have treated C61 as an isolated random manufacturing defect rather than a systemic process failure - a miscalculation that would prove costly in January 2026.

4. The Return to Flight: Mission PSLV-C62 Profile and Objectives

The PSLV-C62 mission was conceived as a high-stakes comeback. It was not only a verification flight to prove the PSLV's reliability was restored but also a commercially and strategically dense mission managed by NewSpace India Limited (NSIL).

4.1 Vehicle Configuration

For this mission, ISRO utilized the PSLV-DL (Dual Launch) variant. This configuration features two strap-on boosters (PSOM-XL) attached to the first stage, bridging the gap between the Core Alone (CA) version and the heavy-lift XL version (with six boosters). The choice of the DL variant indicates a payload mass requirement that necessitated intermediate thrust augmentation.

4.2 The Payload Manifest

The mission carried a total of 16 payloads, a mix of high-value strategic assets and experimental commercial satellites.

Primary Payload: EOS-N1 (Anvesha)

The centerpiece of the mission was EOS-N1, also known as Anvesha. Developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), this 400+ kg satellite was a sophisticated Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) platform designed for strategic surveillance. Unlike standard optical cameras, Anvesha was built to "see" in hundreds of narrow spectral bands, enabling it to break camouflage and identify materials on the ground - capabilities vital for national security.

Secondary Payloads

The 15 co-passenger satellites highlighted the growing diversity of India's space ecosystem and its international partnerships:

AayulSAT (India): Developed by OrbitAID Aerospace, this was a landmark technology demonstrator for on-orbit satellite refueling, a capability currently dominated by major powers like the US and China.

Munal (Nepal): A satellite developed by Nepal’s Antharkshya Pratishtan with assistance from the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, symbolizing space diplomacy.

KID (Spain): The Kestrel Initial Demonstrator by Orbital Paradigm, a prototype for a reusable re-entry capsule.

Dhruva Space Payloads (India): A suite of satellites including Thybolt-3 and LEAP-TD, designed to validate private sector satellite bus platforms.

International CubeSats: Various payloads from the UK, France, and Brazil.

The mission profile called for these satellites to be injected into a Sun-Synchronous Polar Orbit (SSPO) at an altitude of approximately 505 km with an inclination of 97.5 degrees.

5. The Incident: Detailed Reconstruction of the January 12, 2026 Anomaly

On the morning of January 12, 2026, the PSLV-C62 lifted off from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre at 10:17 AM IST. The launch sequence began nominally, lulling mission controllers and the public into a false sense of security.

5.1 Nominal Ascent Phase

The flight timeline followed the standard PSLV trajectory:

T+0:00: Ignition of the S139 First Stage and strap-on boosters. Lift-off was normal.

Boost Phase: The strap-ons separated cleanly, followed by the burnout and separation of the first stage.

PS2 Phase: The liquid-fueled Vikas engine of the second stage ignited and performed nominally. The payload fairing (heat shield) separated as the vehicle exited the dense atmosphere, exposing the EOS-N1 and other satellites to space.

PS2 Separation: The second stage shut down and separated as planned, handing over control to the third stage.

5.2 The Third Stage Anomaly

The anomaly occurred during the operation of the PS3 stage. Approximately eight minutes into the flight, telemetry screens at the Mission Control Centre (MCC) ceased updating nominal parameters.

ISRO Chairman V. Narayanan (Somanath) later described the sequence: "The performance of the vehicle close to the end of the third stage was as expected. Close to the end of the third stage we are seeing more disturbance in the vehicle. Subsequently, there is a deviation in the vehicle observed in the flight path".

Two specific telemetry signatures defined the failure:

Chamber Pressure Drop: Just as in the C61 mission, the pressure within the PS3 motor combustion chamber dropped unexpectedly.

Roll Rate Disturbance: Controllers observed a "disturbance in roll rates". The vehicle began to spin or oscillate around its longitudinal axis beyond the control authority of the RCS.

5.3 Terminal Phase

The combination of reduced thrust (due to pressure drop) and attitude instability (roll disturbance) meant the vehicle could not attain orbital velocity. The navigation guidance system likely detected the deviation and the inability to reach the target orbit. The rocket and its 16 satellites followed a ballistic, sub-orbital trajectory, re-entering the Earth's atmosphere and disintegrating. Any surviving debris would have impacted the ocean, likely in the remote southern Indian Ocean or Pacific.

6. Technical Forensics: Solid Rocket Motor Failure Modes and the S-7 Analysis

The recurrence of the chamber pressure drop combined with roll disturbance provides a strong forensic footprint for identifying the failure mode within the S-7 solid motor.

6.1 Internal Ballistics of Solid Motors

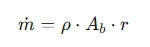

In a solid rocket motor, thrust is a function of the mass flow rate of the exhaust gases, which is governed by the burning rate of the propellant and the geometry of the nozzle throat. The mass flow rate dot{m} is defined as:

Where rho is the propellant density, A_b is the burning surface area, and r is the burn rate.

A drop in chamber pressure indicates that the mass flow rate has decreased, or the nozzle throat area has effectively increased.

6.2 Hypothesis 1: Nozzle Throat Erosion or Structural Failure

The most plausible explanation for a simultaneous pressure drop and roll disturbance is a failure of the nozzle assembly.

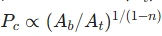

Mechanism: The S-7 uses a submerged flex nozzle. If the graphite or carbon-carbon throat insert erodes excessively or fractures, the throat area (A_t) increases. According to the internal ballistics equation, an increase in throat area causes a precipitous drop in chamber pressure (P_c)

Roll Link: If the nozzle fracture is asymmetric, or if the flex seal fails causing the nozzle to cock to one side, it would generate a massive side force. Since the PS3 relies on the PS4's small thrusters for roll control, a large asymmetric torque from the main engine would easily overwhelm the roll control system, leading to the observed roll rate disturbance.

6.3 Hypothesis 2: Case Burn-Through (Insulation Failure)

Another strong possibility is a breach in the motor casing due to thermal insulation failure.

Mechanism: The propellant is burning at thousands of degrees. The composite casing is protected by a thermal liner. If this liner fails (due to poor bonding or manufacturing defect), the hot gas reaches the casing, weakening it until it ruptures.

Telemetry Signature: A hole in the side of the casing would vent high-pressure gas laterally. This venting acts as a side thruster, inducing a violent roll/yaw tumble. Simultaneously, the venting of gas through the breach reduces the pressure available at the main nozzle, causing the observed P_c drop.

6.4 Hypothesis 3: Propellant Debonding

Debonding occurs when the propellant grain separates from the casing or insulation.

Mechanism: This usually increases the burning surface area (A_b) initially, leading to a pressure spike. However, if the burn front reaches the wall and causes a rupture (as in Hypothesis 2), it results in a pressure drop. The fact that the failure happened "close to the end" of the burn suggests a progressive failure mode like erosion or a burn-through that took time to manifest.

6.5 The "Structural Reinforcement" Fallacy

ISRO stated that "structural reinforcements" were applied after C61. This suggests the C61 investigation concluded the casing or nozzle interface was structurally weak. The failure of C62 despite these reinforcements implies either:

The reinforcement was applied to the wrong area.

The root cause was not structural design but material quality (e.g., a bad batch of resin, fiber, or propellant) which structural patches cannot fix.

7. Strategic Implications: The Loss of the EOS-N1 and EOS-09 Surveillance Assets

The technical failure has catalyzed a severe security deficit. The consecutive loss of EOS-09 and EOS-N1 dismantles a key portion of India’s planned space-based surveillance architecture.

7.1 EOS-N1 (Anvesha): The Hyperspectral Void

The loss of EOS-N1 is particularly damaging. Developed by DRDO, this satellite was equipped with Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) sensors.

The Technology: While conventional satellites (like Cartosat) see in 3-4 broad bands of light (Red, Green, Blue, Near-IR), Hyperspectral sensors divide the spectrum into hundreds of narrow, continuous bands.

Tactical Application: This allows for the spectral fingerprinting of materials. Anvesha was designed to differentiate between:

Live vegetation vs. green camouflage nets.

Real tanks vs. wooden/inflatable decoys.

Disturbed soil (fresh digging) vs. compacted soil (old paths).

Security Context: Along the highly militarized Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China, where concealment and deception are standard doctrines, the ability to unmask camouflaged positions from 500 km away is invaluable. The loss of Anvesha blinds Indian intelligence to these subtle spectral cues, forcing reliance on lower-fidelity optical data or foreign intelligence sharing.

7.2 EOS-09: The Radar Gap

The earlier loss of EOS-09 in May 2025 exacerbates the situation. EOS-09 was a Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellite.

The Technology: SAR transmits its own microwave pulses and reads the reflection, allowing it to image the Earth day or night and through cloud cover.

Operational Necessity: The Himalayan border regions are often obscured by clouds, fog, or snow. Optical satellites (like Cartosat) are blind in these conditions. SAR is the only way to monitor troop movements during the monsoon or winter.

Compound Failure: Losing both the all-weather eye (EOS-09) and the material discriminator (EOS-N1) within 8 months leaves a massive gap in India's Integrated Intelligence Grid. Rebuilding these assets will take 18-24 months and require fresh budgetary approvals, costing the state not just money but critical time.

8. Commercial and Technological Impact: The Loss of Secondary Payloads

Beyond the strategic blow, the failure has decimated a cohort of commercial and diplomatic payloads, stalling key technological advancements.

8.1 AayulSAT: A Setback for In-Orbit Servicing

OrbitAID Aerospace’s AayulSAT was one of the most significant commercial payloads lost. It was designed to demonstrate on-orbit refueling technology.

Significance: The ability to refuel satellites extends their lifespan and reduces space debris. This is a frontier technology currently being pursued by major powers. AayulSAT was attempting to perform fluid transfer experiments in microgravity.

Impact: Its loss delays India's entry into the On-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing (OSAM) market. OrbitAID must now rebuild the payload and wait for a future launch slot, pushing their roadmap back by at least a year.

8.2 Munal: A Diplomatic Loss

The Munal satellite was a flagship project for Nepal, developed with Indian assistance to build capacity in Nepal’s nascent space sector.

Diplomacy: Space diplomacy is a key tool for India to counter Chinese influence in South Asia. The successful launch of Munal was intended to showcase India as a reliable partner for the high-tech needs of its neighbors.

Fallout: The destruction of the satellite is an unfortunate diplomatic hiccup. While the financial cost is low compared to Anvesha, the optics of failing to deliver a neighbor's payload are damaging.

8.3 Dhruva Space and the Startups

Dhruva Space, a leading Indian space startup, lost multiple payloads, including Thybolt-3 and LEAP-TD. These missions were critical for qualifying their satellite platforms (P-DoT and P-30) for global customers. The loss of these heritage missions (missions that prove a system works in space) makes it harder for startups to sell their technology to risk-averse clients.

9. The Economic Fallout: NSIL, Insurance Markets, and the NewSpace Sector

The financial repercussions of the PSLV-C62 failure are multidimensional, affecting the state exchequer, the commercial arm NSIL, and the global insurance market.

9.1 Direct Financial Losses

The combined financial loss of the PSLV-C61 and C62 failures is estimated to be in the range of ₹2,000 Crore to ₹2,500 Crore (approx. $240-$300 Million USD).

Hardware Loss: This includes the cost of two PSLV launch vehicles (approx. ₹200 Crore each), the expensive EOS-09 (₹850 Crore), and the highly complex EOS-N1 (Anvesha), likely valued similarly or higher due to its hyperspectral sensors.

NSIL Revenue: NSIL operates on a commercial basis. The failure to deliver 15 commercial payloads means lost revenue and potential penalties or re-flight obligations, depending on the contracts.

9.2 The Insurance Shock

The global space insurance market is highly sensitive to reliability metrics.

Premium Hikes: Prior to 2025, the PSLV was considered a low-risk vehicle, commanding low insurance premiums (typically <5%). With two failures in three flights, the vehicle's statistical reliability has dropped from >95% to ~93.7%.3 Underwriters will likely increase premiums for future PSLV missions by 20-30%.

Commercial Competitiveness: Higher insurance premiums increase the total cost of launch for customers. This erodes the PSLV's price advantage against competitors like SpaceX’s Transporter missions (which offer extremely low pricing) and Rocket Lab’s Electron. This could drive international small-satellite customers away from NSIL.

9.3 Self-Insurance and State Burden

Crucially, the Indian government typically self-insures its strategic satellites (like EOS-N1). This means there is no insurance payout to cover the loss of the DRDO satellite. The entire cost of replacement must be borne by the Indian taxpayer through new budgetary allocations, diverting funds from other critical defense or development projects.

10. Institutional Diagnostics: Quality Assurance, Transparency, and Crisis Management

The most disturbing aspect of the C62 failure is the implication of institutional lapses within ISRO.

10.1 The "Secret" C61 Report

The investigation report for the PSLV-C61 failure (May 2025) was never made public. It was submitted to the Prime Minister's Office but kept classified.

Lack of Scrutiny: By keeping the report internal, ISRO avoided external peer review of its failure analysis. The scientific community and industry stakeholders could not verify if the "structural reinforcements" were an adequate solution.

Normalization of Deviance: The decision to rush the C62 launch only eight months after a major failure - without a clear, publicly validated fix - suggests a culture where schedule pressure may have overridden engineering caution. This phenomenon, known as the "normalization of deviance," has historically been the cause of major aerospace disasters (e.g., Space Shuttle Challenger).

10.2 Quality Control in the Supply Chain

The recurrence of the third-stage failure points to a "manufacturing rot" or quality control (QC) lapse in the solid motor supply chain.

Batch Defects: Solid motors are often produced in batches. It is highly probable that the S-7 motors for C61 and C62 came from the same production run or used the same batch of raw materials (propellant/binder). If the QC protocols failed to detect a flaw in the raw materials (e.g., impurities in the HTPB or weak bonding agents), the entire batch effectively became ticking time bombs.

Implications for Gaganyaan: The PSLV's solid motor technology is shared with the GSLV Mk III (LVM3), which uses massive S200 solid boosters. A systemic failure in solid motor QC poses a terrifying risk to the Gaganyaan human spaceflight mission. If ISRO cannot guarantee the reliability of the smaller S-7 motor, confidence in the man-rated S200 boosters is severely undermined.

11. Future Trajectory and Remediation

The PSLV fleet is now effectively grounded until the root cause is definitively identified and rectified. The path forward will be arduous.

11.1 Technical Remediation

Ground Testing: ISRO must conduct static fire tests of the remaining S-7 inventory to see if the "pressure drop" can be replicated on the ground. This is expensive but necessary to validate the batch quality.

Design Review: A complete review of the S-7 motor design may be required, particularly the nozzle throat materials and the insulation bonding process. The structural reinforcements applied after C61 must be re-evaluated as ineffective.

11.2 Strategic Adjustments

Payload Migration: To avoid further delays in deploying critical satellites, ISRO may need to shift payloads to the LVM3 or the developing SSLV (Small Satellite Launch Vehicle). However, LVM3 is expensive and reserved for heavy payloads, while SSLV has limited capacity.

Transparency: To restore global confidence, ISRO must release a redacted version of the C61 and C62 failure reports. Transparency is the only way to reassure the insurance market and commercial customers that the problem is understood and solved.

11.3 Conclusion

The failure of PSLV-C62 is a watershed moment for Indian spaceflight. It has shattered the aura of invincibility surrounding the "Workhorse" PSLV and exposed deep fissures in the quality assurance and crisis management frameworks of the agency. The loss of EOS-N1 and EOS-09 leaves India strategically vulnerable, while the economic fallout threatens the momentum of the New Space sector. ISRO faces a difficult road ahead: it must prioritize engineering rigor over launch cadence, embrace transparency over secrecy, and fundamentally overhaul its solid propulsion manufacturing processes. The cost of a third failure would be existential; the "Workhorse" must be healed, or it must be retired.

12. Comprehensive Data Tables

Table 1: Technical Comparison of PSLV-C61 and PSLV-C62 Failures

Parameter | PSLV-C61 | PSLV-C62 |

Launch Date | May 18, 2025 | January 12, 2026 |

Vehicle Variant | PSLV-XL (presumed) | PSLV-DL (2 Strap-ons) |

Primary Payload | EOS-09 (Radar Imaging) | EOS-N1 / Anvesha (Hyperspectral) |

Failure Phase | Third Stage (PS3) | Third Stage (PS3) |

Telemetry Signature | Drop in Chamber Pressure (P_c) | Drop in P_c + Roll Rate Disturbance |

Corrective Action (Pre-flight) | N/A | "Structural Reinforcements" (Failed) |

Investigation Status | Report Submitted to PMO (Classified) | FAC Initiated |

Table 2: Detailed Payload Manifest and Loss Assessment (PSLV-C62)

Payload Name | Developer | Origin | Function | Impact of Loss |

EOS-N1 (Anvesha) | DRDO | India | Strategic Hyperspectral Surveillance | Critical: Loss of anti-camouflage capability for border security. |

AayulSAT | OrbitAID Aerospace | India | On-Orbit Refueling Demonstrator | High: Delays India's entry into the satellite servicing market. |

Munal | NAST / MEA | Nepal | Earth Observation / Capacity Building | Diplomatic: Setback for Indo-Nepal space cooperation. |

KID | Orbital Paradigm | Spain | Re-entry Vehicle Prototype | R&D: Loss of flight data for European reusable logistics. |

Thybolt-3 | Dhruva Space | India | Communication / Tech Demo | Commercial: Delays validation of Dhruva's P-DoT satellite bus. |

MOI-1 | TakeMe2Space | India | Orbital Edge Computing (AI) | Commercial: Setback in competition with Google's Project Sun Catcher. |

LEAP-TD | Dhruva Space | India | Technology Demonstrator | Commercial: Loss of heritage data for satellite subsystems. |

Table 3: Estimated Financial Impact of Recent PSLV Failures

Item | Estimated Value (INR) | Estimated Value (USD) | Notes |

EOS-09 Satellite | ₹850 Crore | ~$100 Million | Based on RISAT series costs. |

EOS-N1 Satellite | ₹1,000+ Crore | ~$120 Million | Hyperspectral sensors are highly complex/expensive. |

PSLV Launch Vehicles (x2) | ₹400 Crore | ~$48 Million | Approx. ₹200 Cr per launch. |

Commercial Payload Value | ₹200-300 Crore | ~$30 Million | Est. value of 15+ co-passenger satellites. |

Total Direct Loss | ~₹2,500 Crore | ~$300 Million | Excludes opportunity costs and insurance premium hikes. |

Join our WhatsApp and Telegram Channels

Get Knowledge Gainers updates on our WhatsApp and Telegram Channels