Introduction:

The transmission of electrical energy without the medium of solid conductors—Wireless Power Transmission (WPT)—stands as one of the most transformative yet contentious technological frontiers of the 21st century. What began as a Victorian-era dream of illuminating the globe without wires has evolved, by 2025, into a sophisticated ecosystem of near-field resonant charging pads, far-field microwave beams, and orbital solar arrays. This report provides an exhaustive examination of the WPT landscape. It dissects the electromagnetic physics governing the "air gap," traces the historical lineage from the high-voltage experiments of Nikola Tesla to the silicon-driven innovations of the modern era, and rigorously evaluates the biological and environmental implications of saturating the biosphere with anthropogenic fields. Furthermore, it analyzes the commercial and military breakthroughs of 2025 and 2026, weighing the economic efficiency of wireless infrastructure against the ecological imperatives of energy conservation and wildlife protection.

1. The Physics of Invisible Energy: Mechanisms of Transfer

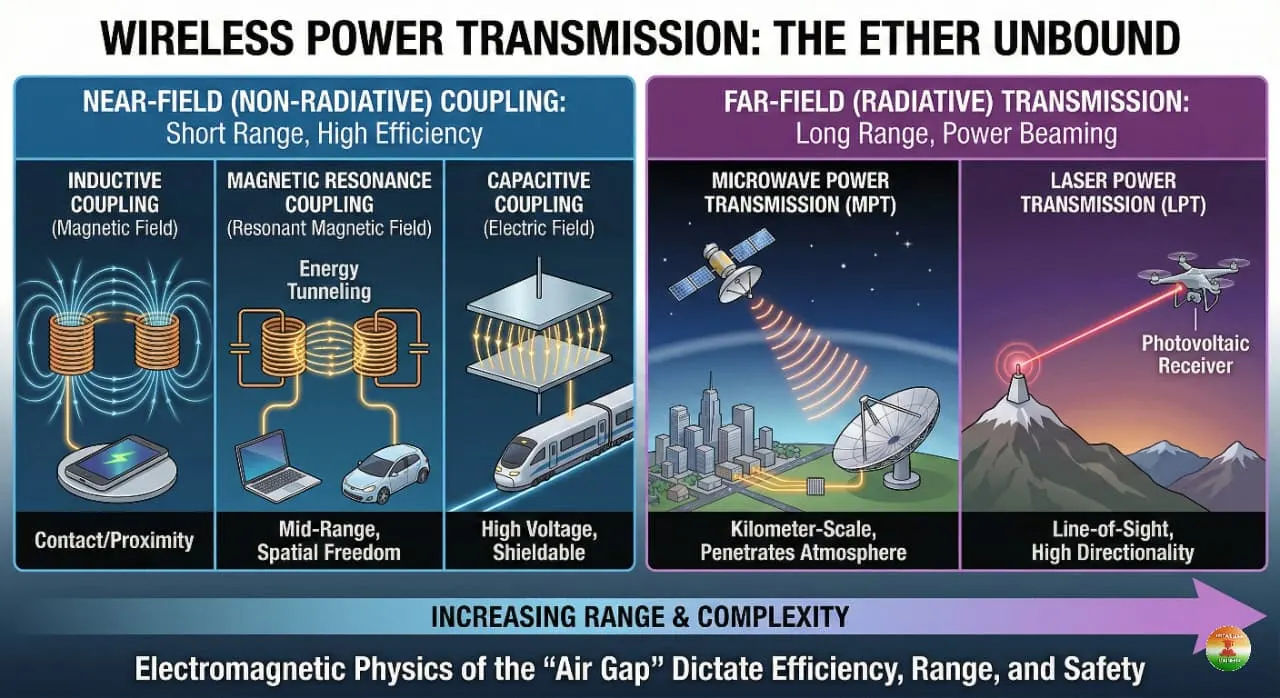

To comprehend the capabilities and the inherent limitations of modern WPT systems, one must first distinguish between the two fundamental modes of operation: near-field (non-radiative) and far-field (radiative) transmission. These categories are defined not merely by the physical distance between the transmitter and receiver, but by the behavior of the electromagnetic fields relative to the wavelength ($\lambda$) of the frequency employed. The physics of the "air gap" dictates everything from the efficiency of an electric vehicle charger to the safety of a microwave power beam.

1.1 Near-Field Non-Radiative Coupling

The near-field region exists within approximately one wavelength ($D < \lambda$) of the transmitting antenna. In this region, energy is stored in oscillating magnetic or electric fields rather than propagating outward as electromagnetic waves. If a receiver is not present to couple with this field, the energy effectively collapses back into the source, minimizing power loss to the surrounding environment. This characteristic makes near-field systems highly efficient for short-range applications but limits their utility for long-distance transmission.

1.1.1 Inductive Coupling

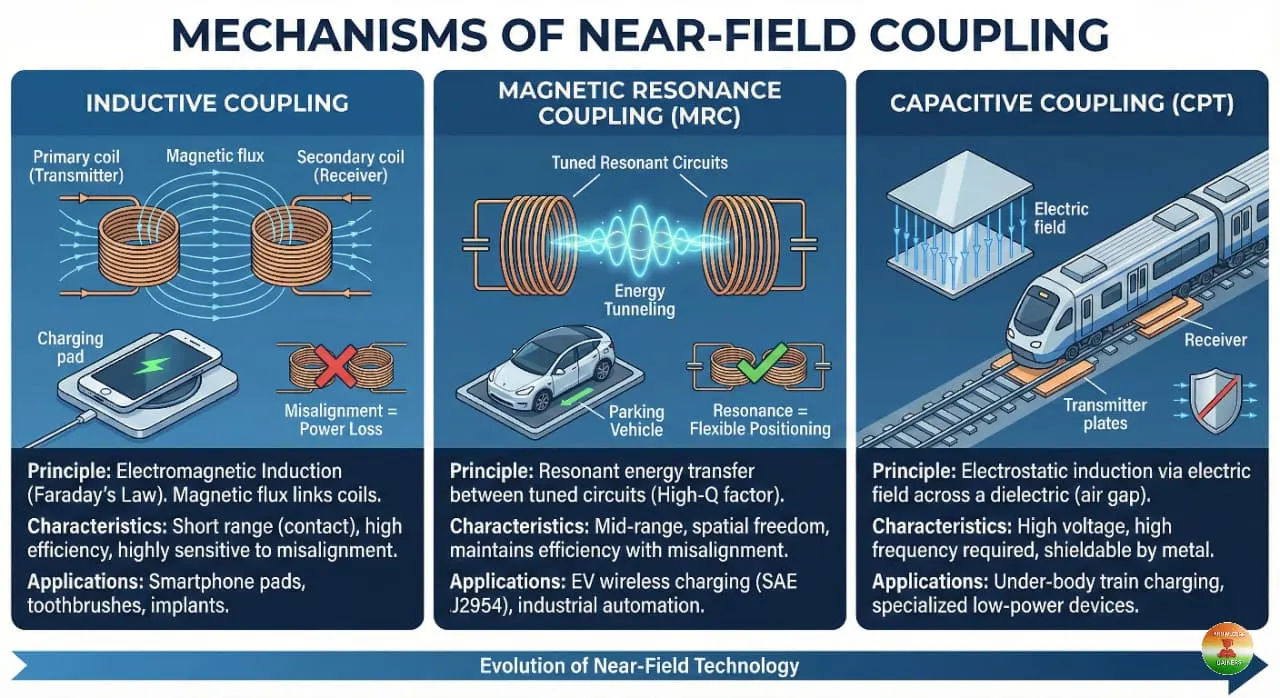

Inductive coupling is the foundational mechanism for most short-range commercial applications, including smartphone charging pads, electric toothbrushes, and medical implants. It operates on the principle of electromagnetic induction, a phenomenon first quantified by Michael Faraday in 1831.

In a standard inductive system, a primary coil (the transmitter) is driven by an alternating current (AC), creating an oscillating magnetic field. When a secondary coil (the receiver) is placed within this field, the magnetic flux lines cut through the turns of the receiver coil, inducing an electromotive force (EMF) or voltage according to Faraday’s Law of Induction. The efficiency of this transfer is governed by the coupling coefficient ($k$), which represents the fraction of magnetic flux generated by the primary coil that successfully links to the secondary coil.

However, the physics of magnetic fields impose strict limitations. The magnetic field strength generated by a loop of wire decays at a rate of $1/r^3$, meaning that the energy density drops precipitously with distance. Even a misalignment of a few centimeters or a slight increase in the vertical gap can cause the coupling coefficient to plummet, severing the power link. This rapid decay restricts traditional inductive coupling to "contact" or very close proximity charging, where the coils must be perfectly aligned to achieve acceptable efficiency.

1.1.2 Magnetic Resonance Coupling (MRC)

To overcome the strict positioning requirements of simple induction, researchers developed Magnetic Resonance Coupling (MRC), also known as Resonant Inductive Coupling. This technique utilizes two coils that are tuned to resonate at the identical frequency, much like two tuning forks vibrating in sympathy.

By adding compensation capacitors to the inductive circuits, engineers create a resonant tank circuit with a high Quality Factor ($Q$). The $Q$ factor describes the ratio of energy stored in the oscillating system to the energy dissipated per cycle. In a high-$Q$ system, energy tunnels between the two resonant objects with high efficiency, even if the coupling coefficient ($k$) is relatively low due to distance. This allows for "mid-range" transfer—typically several times the diameter of the coils—and affords the user significant spatial freedom.

MRC is the dominant technology for modern high-power applications, particularly Electric Vehicle (EV) wireless charging. The SAE J2954 standard, which governs wireless EV charging, relies on resonance to allow vehicles to charge efficiently (88–93%) even if the driver does not park perfectly centered over the ground pad. The resonance allows the magnetic field to "stretch" across the air gap (Z-class gaps of 100–250 mm) while maintaining high power transfer rates.

1.1.3 Capacitive Coupling (CPT)

While inductive systems utilize magnetic fields, Capacitive Power Transfer (CPT) utilizes electric fields. In this configuration, the transmitter and receiver plates form a capacitor, with the intervening air gap acting as the dielectric medium. An alternating voltage applied to the transmitter plate creates an oscillating electric field that induces an alternating potential on the receiver plate via electrostatic induction.

CPT offers distinct advantages in specific scenarios. Unlike magnetic fields, electric fields can be easily shielded by metal, potentially reducing electromagnetic interference (EMI) in surrounding electronics. However, because the capacitance formed by two plates across an air gap is typically very small (in the picofarad range), CPT systems require very high voltages and high frequencies to transfer significant power. Research into CPT has accelerated for applications such as under-body train charging, where the large surface area of the train's undercarriage can serve as a receiver plate, potentially reducing the weight and cost associated with the heavy ferrite cores required for inductive systems.

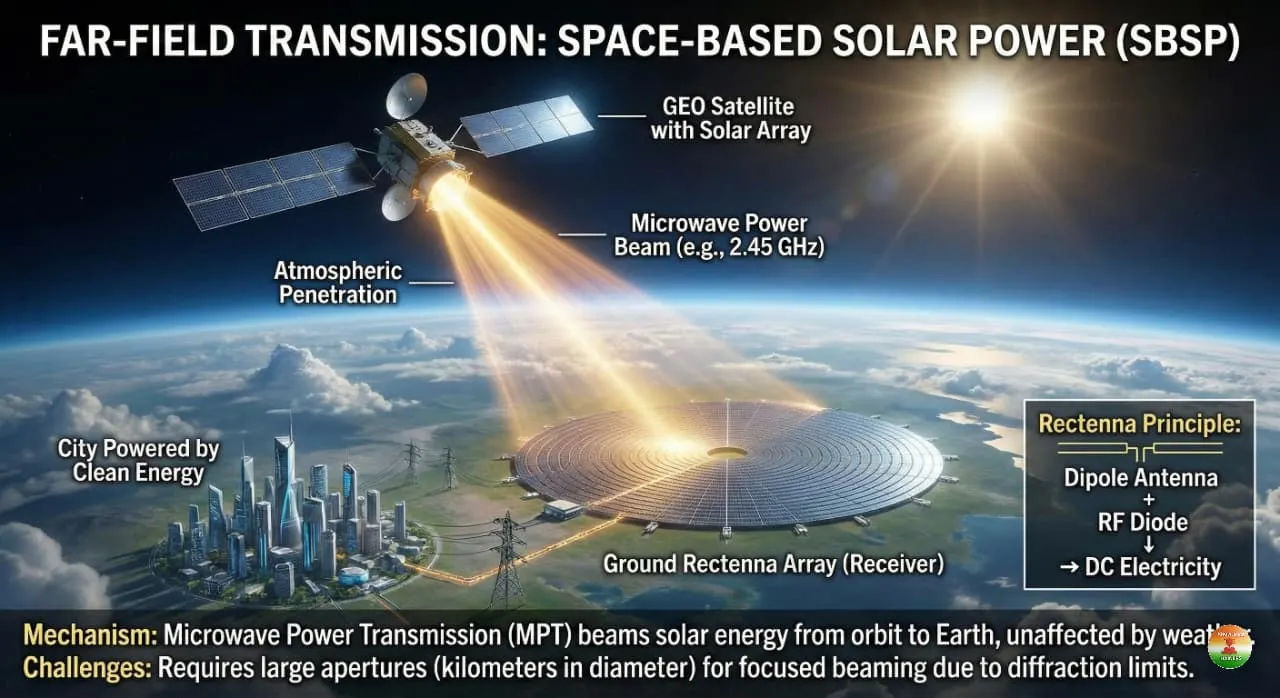

1.2 Far-Field Radiative Transmission (Power Beaming)

Far-field transmission, often referred to as power beaming, occurs at distances much greater than the wavelength ($D \gg \lambda$). In this regime, the electromagnetic field detaches from the antenna and propagates through space as a transverse electromagnetic wave. Unlike near-field systems, where energy is stored, far-field systems radiate energy continuously. This allows for transmission over kilometer-scale distances but introduces significant challenges regarding efficiency, aiming, and safety.

1.2.1 Microwave Power Transmission (MPT)

Microwave Power Transmission involves converting electricity into microwaves—typically at frequencies such as 2.45 GHz or 5.8 GHz—beaming them via a transmitting antenna (often a phased array), and capturing them using a "rectenna" (rectifying antenna). The rectenna is a specialized component composed of a dipole antenna with an RF diode connected across the dipole elements. The diode rectifies the AC microwave signal into Direct Current (DC) electricity.

Microwaves possess unique characteristics that make them suitable for specific applications, most notably Space-Based Solar Power (SBSP). Microwaves at 2.45 GHz can penetrate clouds, rain, and atmospheric dust with relatively low attenuation, ensuring reliable power delivery regardless of weather conditions. However, the physics of diffraction imposes a lower limit on the size of the antennas. To keep a microwave beam focused over long distances (e.g., from geostationary orbit to Earth), the transmitting aperture and the receiving rectenna must be kilometers in diameter to minimize beam divergence.

1.2.2 Laser Power Transmission (LPT)

Laser Power Transmission (LPT) utilizes coherent light beams, typically in the infrared spectrum, to transmit energy to photovoltaic receivers. Lasers offer the advantage of extreme directionality; due to their short wavelength, laser beams have much lower divergence than microwaves. This allows for the use of compact transmitters and receivers, making LPT ideal for powering remote sensors, drones, or lunar rovers where size and weight are critical constraints.

However, laser transmission is inherently strictly line-of-sight and is highly sensitive to atmospheric conditions. The phenomenon of "thermal blooming" occurs when a high-power laser beam heats the air through which it passes. This heating changes the refractive index of the air, creating a lens effect that defocuses the beam and reduces power density at the receiver. Furthermore, fog, rain, and turbulence can scatter the laser light, significantly degrading efficiency. To combat this, modern LPT systems employ "adaptive optics"—deformable mirrors that adjust hundreds of times per second to compensate for atmospheric distortion—and "beam dithering" techniques that rapidly move the beam to prevent localized heating of the air path.

1.3 Table: Comparative Analysis of WPT Modalities

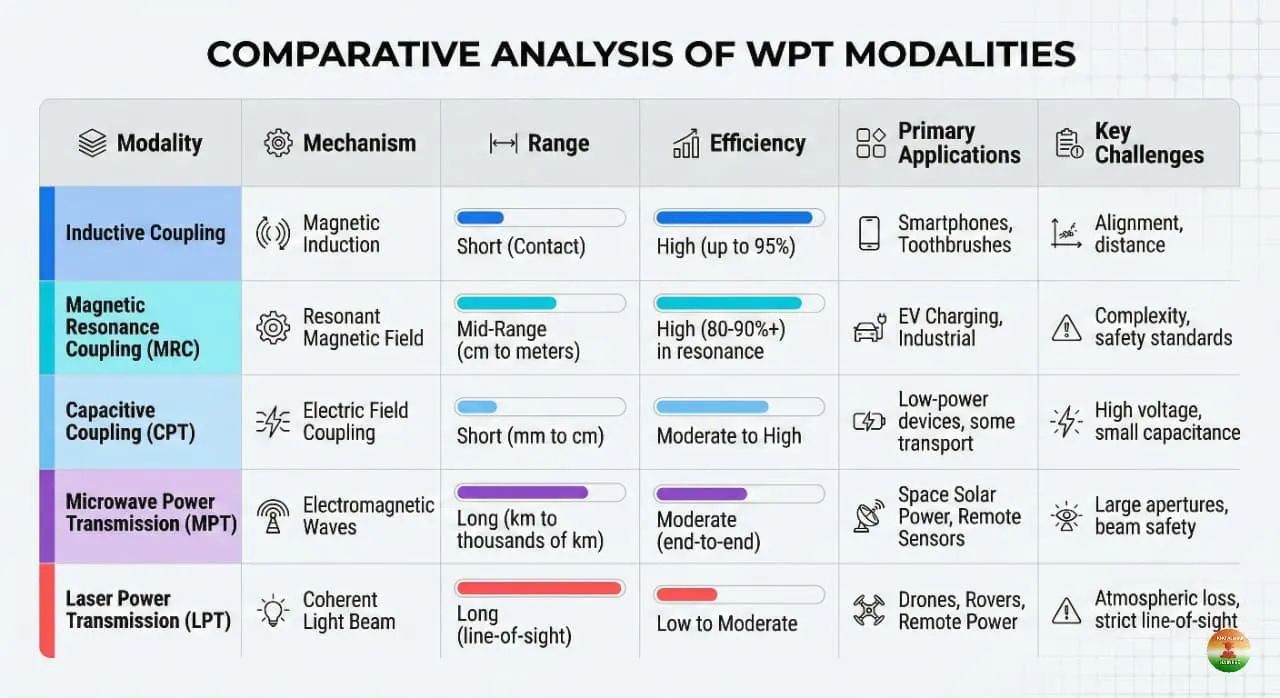

Feature | Inductive Coupling | Magnetic Resonance (MRC) | Microwave Beaming (MPT) | Laser Beaming (LPT) |

Physics Regime | Near-field (Magnetic) | Near-field (Magnetic) | Far-field (EM Wave) | Far-field (Optical) |

Effective Range | Very Short (< 1 cm) | Mid-range (10 cm – 2 m) | Long (km to Orbit) | Long (km to Space) |

Efficiency | High (>90%) | High (80-90%) | Moderate (End-to-End) | Low to Moderate |

Key Limitation | Alignment sensitivity | Distance ($1/r^3$ decay) | Diffraction / Aperture Size | Atmospheric Attenuation |

Safety Profile | High (Field contained) | High (Field contained) | Exclusion zones required | Eye safety / Burns |

Primary Use Case | Phones, Toothbrushes | EVs, Implants, Industrial | Space Solar, Drones | Military, Rovers, Sensors |

2. The Historical Odyssey: From Wardenclyffe to Silicon Valley

The trajectory of wireless power transmission is a saga of visionary overreach, lengthy dormancy, and eventual pragmatic resurgence. It is a history that mirrors the broader evolution of electrical engineering, shifting from the brute-force experimentation of the 19th century to the precision-tuned solid-state electronics of the 21st.

2.1 The Tesla Era: A World System Unfulfilled (1891–1917)

While Heinrich Hertz demonstrated the existence of electromagnetic waves in 1887, it was Nikola Tesla who first conceived of using these waves not merely for communication, but for the transmission of industrial-scale power. Tesla is universally recognized as the father of wireless power, and his work in the late 19th century laid the conceptual groundwork for the field.

Tesla’s journey began with the invention of the Tesla Coil in 1891, a resonant transformer circuit capable of producing high-voltage, high-frequency alternating currents. This device allowed him to demonstrate the illumination of Geissler tubes (precursors to neon lights) without wires, proving that energy could travel through space via an electrostatic field.

2.1.1 Colorado Springs and the Earth Resonance Theory (1899)

In 1899, Tesla established a high-altitude laboratory in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He chose this location for its elevation (over 6,000 feet) and the frequency of lightning storms, which he intended to study. Here, Tesla formulated his theory of terrestrial resonance. He believed that the Earth itself could act as a giant conductor. By injecting high-frequency current into the ground at the planet's resonant frequency, he theorized he could create a standing wave of electrical charge. A receiver tuned to this frequency anywhere on the globe could then tap into this energy, much like a radio tuning into a station.

During his time in Colorado, Tesla constructed a massive magnifying transmitter and claimed to have successfully powered light bulbs placed in the ground significantly distant from the lab, although the precise technical verification of these claims remains a subject of historical debate. He also recorded stationary waves produced by lightning discharges, which convinced him that the Earth was indeed a conductive body capable of sustaining global oscillations.

2.1.2 The Wardenclyffe Tower (1901–1917)

Empowered by his findings, Tesla returned to New York and secured funding from financier J.P. Morgan to construct the Wardenclyffe Tower on Long Island. Designed by architect Stanford White, the 187-foot tower topped with a 68-foot copper dome was intended to be the hub of a "World Wireless System." Tesla envisioned this facility transmitting not just news, stock quotes, and secure military communications, but also electrical power to any point on Earth.

However, the project was doomed by a combination of economics and physics. In 1901, Guglielmo Marconi successfully transmitted a radio signal across the Atlantic using a much simpler, cheaper system. Marconi focused solely on communication, which required vastly less power than Tesla’s industrial ambitions. J.P. Morgan, seeing Marconi’s success and doubting the commercial viability of free global power (which would be impossible to meter and monetize), withdrew his support. Tesla struggled for years to find new investors, but the tower was never completed. In 1917, heavily in debt, Tesla saw his dream dismantled when the tower was dynamited for scrap metal.

2.2 The Microwave Era and the Space Race (1960s–1980s)

Following Tesla’s death in 1943, high-power wireless research entered a period of dormancy until the dawn of the Space Age. The focus shifted from Tesla’s earth-resonance theories to the use of directed microwave beams.

The pivotal figure of this era was William C. Brown of Raytheon. In the early 1960s, Brown invented the rectenna, the device capable of converting microwaves back into DC electricity with high efficiency. In 1964, Brown orchestrated a historic demonstration on CBS News: a microwave-powered helicopter. The small aircraft was kept aloft solely by a microwave beam transmitted from the ground, proving that wireless power could sustain mechanical work indefinitely.

This success coincided with the energy crises of the 1970s, prompting NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to investigate Peter Glaser’s concept of the Solar Power Satellite (SPS). The proposal involved launching massive solar arrays into orbit and beaming the energy down to Earth via microwaves. While the physics were sound—and verified by Brown’s work—the sheer cost of launching thousands of tons of hardware into space rendered the project economically impossible at the time.

2.3 The Modern Resurgence (2007–Present)

The modern era of commercial wireless power began in 2007, driven by the ubiquity of mobile electronics. A team at MIT, led by Professor Marin Soljačić, demonstrated "WiTricity"—lighting a 60-watt bulb from a distance of 2 meters with roughly 40% efficiency.

Crucially, the MIT team utilized magnetic resonance coupling, proving that non-radiative fields could transfer useful amounts of power over mid-range distances without the dangers associated with microwave beams. This breakthrough catalyzed the formation of the Wireless Power Consortium (WPC) and the AirFuel Alliance, leading to the "format wars" between the Qi and PMA standards. By 2017, Apple’s adoption of the Qi standard for the iPhone unified the market, making inductive charging a standard feature in consumer electronics.

Simultaneously, the automotive industry began standardizing high-power wireless charging. The release of the SAE J2954 standard in 2020 provided the technical framework for charging electric vehicles at up to 11 kW wirelessly, setting the stage for the infrastructure rollouts seen in 2025.

3. Modern Technological Frontiers (2025-2026)

As of late 2025, the WPT market has moved beyond smartphone charging into critical infrastructure and defense. The sector is defined by a race to commercialize "Air Charging" (power at a distance) and "Dynamic Charging" (power in motion), with significant leaps in efficiency and range.

3.1 Long-Range Power Beaming: Breaking Records

In 2025, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) achieved a watershed moment in its POWER (Persistent Optical Wireless Energy Relay) program.

The 8.6 km Record: During the PRAD (POWER Receiver Array Demo) tests at White Sands Missile Range, researchers successfully beamed 800 watts of optical power over a distance of 8.6 kilometers (5.3 miles). This far exceeded previous benchmarks which were generally under 2 km.

Technical Breakdown: The system utilized a new receiver design involving parabolic mirrors and high-efficiency photovoltaic cells. Crucially, the test demonstrated the ability to transmit significant power through the thickest part of the atmosphere (ground-to-ground), validating the technology's resilience against atmospheric attenuation.

Strategic Implication: This technology aims to create an "energy web" for military operations, allowing drones and forward operating bases to receive power without fuel convoys, which are historically vulnerable logistical chokepoints.

3.2 Wireless Power Networks (WPN) and the "Battery-Free" IoT

Companies like Energous and Ossia are pioneering the transition from "charging" to "delivery." The goal is to eliminate disposable batteries in the 40 billion IoT devices projected by 2030.

Energous (2025 Status): Energous has pivoted to "Wireless Power Networks" (WPNs). In 2025, they reported a 453% revenue increase, driven by the adoption of their PowerBridge transmitters in retail and logistics. These systems provide "always-on" power to RF tags and sensors, eliminating the labor cost of battery replacement.

Ossia (Cota): Ossia continues to commercialize its Cota technology, which behaves like Wi-Fi for power. In 2025, they focused on universal adapters and retrofitting consumer electronics to receive power over the air. Cota uses a retro-directive technique where the receiver sends a pilot signal, and the transmitter returns power along the exact same path, ensuring power is only delivered to the device and not to people or objects in the room.

Environmental Driver: The EU Battery Regulation 2023/1542, fully enforceable in 2025, mandates strict recycling and sustainability standards for batteries. This regulatory pressure is forcing industries to adopt WPT to avoid the compliance costs associated with battery disposal.

3.3 Automotive Infrastructure and Dynamic Charging

WiTricity and other players have solidified the SAE J2954 standard for EV wireless charging.

Commercial Fleets: The economic case for wireless charging has been proven in transit fleets. Lifecycle analysis in 2025 showed that wireless bus fleets have a lower Total Cost of Ownership ($44.5M) compared to diesel ($60.1M) or plug-in electric ($47.3M). This savings comes from "opportunity charging"—topping up batteries at stops—which allows buses to carry smaller, lighter, and cheaper batteries.

Dynamic WPT (Roadway Charging): While technically feasible, electrifying highways remains expensive ($1.7M–$3.5M per km). However, pilot projects in 2025 (e.g., Indiana, Sweden) are testing this for long-haul trucking corridors where the reduction in battery weight justifies the infrastructure investment.

3.4 Space-Based Solar Power (SBSP): The Ultimate Frontier

Space-Based Solar Power represents the theoretical apex of WPT utility. By placing solar arrays in geostationary orbit, energy can be harvested 24/7 without atmospheric attenuation or the day/night cycle, potentially yielding 8-10 times the yield of terrestrial panels.

Caltech's SSPP: Building on the 2023 success of the MAPLE experiment (which beamed power from orbit to Earth for the first time), Caltech is refining lightweight microwave transmitters.

Aetherflux: A California startup that raised $50 million in 2025. They are deviating from the massive geostationary satellite model, instead planning a constellation of smaller Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites that use infrared lasers to beam power to small ground stations. Their first orbital prototype is scheduled for launch on a SpaceX vehicle in 2026.

International Efforts: China has announced plans for a 1-kilometer-wide solar array. The European Space Agency (ESA) SOLARIS initiative is currently funding research into the health and environmental effects of gigawatt-scale microwave beams.

4. Human Health and Safety: The Great Debate

The expansion of high-power wireless transmission has reignited scientific and public debate regarding the safety of electromagnetic fields (EMF). This discourse is characterized by a stark divide between regulatory bodies relying on thermal standards and independent researchers pointing to biological effects.

4.1 The Regulatory Consensus: Thermal Effects

Organizations like the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) and the FCC base their safety guidelines on the thermal paradigm.

The Principle: RF radiation is considered harmful only if it raises the temperature of human tissue. The specific absorption rate (SAR) limits (e.g., 4 W/kg for whole-body exposure) are set to prevent a core body temperature rise of more than 1°C.

2025 ICNIRP Statement: In 2025, ICNIRP released a statement identifying "gaps in knowledge." They prioritized research into heat-induced pain (specifically at millimeter-wave frequencies used in 6G and WPT) and the thermal dosimetry of the human eye. They explicitly excluded "non-thermal" endpoints like depression unless supported by robust evidence, maintaining their stance that non-thermal mechanisms are unproven.

4.2 The Scientific Dissent: Non-Thermal Effects

A growing body of research challenges the thermal-only view, arguing that EMF can cause biological harm at levels well below those that cause heating.

Oxidative Stress: Independent researchers note that a vast majority (89% of 367 papers analyzed by Henry Lai) show that RF exposure causes oxidative stress—an imbalance of free radicals that can damage DNA and cells. A WHO-EMF review in 2025 dismissed this evidence due to "heterogeneity," a move criticized by dissenting scientists as methodological exclusion.

Carcinogenicity (NTP Study): The National Toxicology Program (NTP) study—the largest of its kind—found "clear evidence" that RF radiation caused malignant schwannomas (heart tumors) and "some evidence" of gliomas (brain tumors) in male rats. Crucially, these effects occurred without significant body heating, directly contradicting the thermal paradigm.

Mechanisms: Proposed non-thermal mechanisms include the disruption of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) in cells, which could alter neurotransmitter release and cellular metabolism.

4.3 Safety in WPT Systems

For commercial WPT systems, safety is managed through beam control and "exclusion zones."

Foreign Object Detection (FOD): EV chargers and resonant pads must instantly cut power if a metal object (which could melt) or a living being enters the field.

Beam Safety: Laser WPT systems (like Aetherflux) must employ safety interlocks that shut off the beam within milliseconds if an object (bird, plane) crosses the line of sight to prevent eye damage or burns.

5. Environmental Impact: A Double-Edged Sword

Wireless power presents a complex environmental paradox: it offers a solution to the global e-waste crisis while simultaneously introducing new electromagnetic pollutants into the biosphere.

5.1 The Positive: E-Waste and Decarbonization

Eliminating Batteries: The proliferation of IoT devices threatens to flood landfills with billions of batteries containing lithium and cobalt. WPT networks (Energous, Ossia) allow devices to be "battery-free," drawing power from the air. Eliminating just half of the projected battery waste could prevent 28 billion batteries from entering landfills annually.

Light-weighting Vehicles: By enabling frequent, opportunistic charging, WPT allows EVs to carry smaller batteries. This reduces the extraction of rare-earth minerals and lowers the energy required to manufacture the vehicle. As noted, a wireless bus can be up to 46% lighter than a long-range battery bus.

5.2 The Negative: Impact on Fauna

The introduction of high-power microwave beams and ubiquitous RF fields poses risks to wildlife, particularly species that rely on magnetoreception.

Magnetoreception Disruption: Migratory birds and insects (like bees) use the Earth's magnetic field for navigation. Research indicates that anthropogenic RF fields can disrupt the cryptochrome photoreceptors in birds' eyes, jamming their internal compass. Studies have shown that bees exposed to RF fields exhibit "worker piping" (a distress signal) and have drastically reduced homing abilities (only 7.3% return rate vs. 39.7% for controls).

Insect Decline: A review of 113 studies found that RF-EMF had significant negative effects on birds and insects in 65% of cases, affecting reproduction and development. There is concern that the rollout of high-frequency WPT and 5G networks acts in synergy with pesticides to accelerate insect population collapse.

5.3 Atmospheric Interaction

High-energy laser beaming faces the physical phenomenon of thermal blooming. As a high-power laser travels through the air, it heats the path, creating a lens effect that defocuses the beam.

Mitigation: 2025 research has focused on beam dithering (rapidly moving the beam to spread heat) and adaptive optics (deforming mirrors to compensate for turbulence) to maintain transmission efficiency during diverse weather conditions.

6. Economic Analysis and Future Outlook

6.1 The "Efficiency Tax"

A critical barrier to WPT adoption is the efficiency loss compared to wires.

The Cost: Inductive EV charging is 88–93% efficient, compared to 95%+ for plug-in. While negligible for a single user ($40/year), at a grid scale, this "efficiency tax" represents gigawatt-hours of wasted energy. Policymakers must weigh the convenience of wireless against the imperative of energy conservation.

6.2 Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

Despite the efficiency loss, the TCO favors wireless in specific sectors. For industrial IoT, the cost of a wireless receiver is far lower than the labor cost of rolling a truck to replace a dead battery in a remote sensor ($300–$600 per visit). For transit, the reduction in vehicle weight and maintenance (no broken plugs) offsets the infrastructure capital.

6.3 The Road Ahead (2026–2030)

2026: Launch of Aetherflux's LEO solar prototype.

2027–2028: Widespread integration of WPT in industrial warehousing and retail (electronic shelf labels).

2030+: Potential deployment of dynamic charging lanes on major freight corridors and pilot testing of utility-scale space solar.

Conclusion

Wireless Power Transmission has matured from a scientific novelty into a versatile infrastructure technology. In 2025, it is reshaping industries by decoupling energy from physical storage (batteries), thereby reducing e-waste and enabling autonomous logistics. However, this progress comes with significant responsibilities.

The dichotomy between the regulatory "thermal paradigm" and the biological evidence of non-thermal harm suggests that safety standards may be lagging behind technological capabilities. As we scale from charging toothbrushes to beaming gigawatts from space, the environmental footprint—measured not just in carbon, but in electromagnetic interference with the biosphere—must be rigorously managed. The future is undoubtedly wireless, but ensuring it is safe for both humans and the ecosystem remains the preeminent engineering challenge of the coming decade.

Join our WhatsApp and Telegram Channels

Get Knowledge Gainers updates on our WhatsApp and Telegram Channels