Part I: The Architecture of Disruption – The New US Trade Regime

The global trading system, once anchored by the multilateral stability of the World Trade Organization (WTO), has fundamentally shifted in the mid-2020s toward a model defined by aggressive unilateralism, executive fiat, and the weaponization of market access. The interim trade agreement between the United States and India, announced in February 2026, cannot be understood in isolation. It is the latest and perhaps most significant artifact of a new "Reciprocal Trade" architecture established by the second Trump administration. This section dissects the structural transformation of US trade policy that precipitated the crisis of 2025 and the subsequent diplomatic recalibration of 2026.

1.1 The Collapse of MFN and the Rise of the "Universal Baseline"

For decades, global commerce relied on the Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) principle, which ensured that the lowest tariff offered to one partner was extended to all. In April 2025, this norm was effectively abandoned by the United States with the declaration of a "national emergency" regarding persistent trade deficits. Invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the administration introduced a "Universal Baseline Tariff" of 10% on all imports, fundamentally altering the cost structure of global supply chains.

This baseline was merely the foundation. The administration’s policy evolved rapidly into a system of "Reciprocal Tariffs," codified in Executive Order 14257. Under this regime, the US tariff rate would mirror the average weighted tariff imposed by a trading partner on US goods. For protectionist economies with high bound rates—such as India—this mathematical reciprocity resulted in punitive US duties far exceeding the global average. By early 2026, the effective average US tariff rate had surged from a historical 2.5% to approximately 16.8%, with peaks reaching 27% during periods of maximum volatility.

This shift represents a move from "rules-based" trade to "power-based" trade. Market access is no longer a right guaranteed by treaty but a privilege negotiated through bilateral transaction. The "Reciprocal Tariff" mechanism serves as both a revenue generator and a coercive tool, designed to force trading partners to lower their own barriers or face exclusion from the world's largest consumer market.

1.2 The Geopolitical Stacking Mechanism

A defining feature of the 2025–2026 trade landscape is the "stacking" of tariffs based on non-trade geopolitical behaviors. The administration has utilized trade policy as the primary instrument of statecraft, overlaying economic duties with national security penalties. This created a composite tariff structure for nations deemed "misaligned" with US strategic interests.

For India, this stacking mechanism created a crisis of unprecedented magnitude in late 2025.

Layer 1: The Reciprocal Baseline. Because India historically maintained high tariffs to protect its domestic agriculture and manufacturing sectors (averaging roughly 18-20% effectively, but higher in bound terms), the US reciprocal calculation initially set a high baseline duty on Indian exports.

Layer 2: The Russian Oil Penalty. In August 2025, the administration issued Executive Order 14329, imposing an additional 25% ad valorem duty on all imports from India. This was explicitly punitive, triggered by India’s continued procurement of discounted crude oil from the Russian Federation, which the White House argued was undermining Western sanctions and funding the war in Ukraine.

By the start of 2026, the aggregate tariff burden on Indian goods entering the United States threatened to reach 50%—a prohibitive level that would have rendered Indian textiles, pharmaceuticals, and light engineering goods uncompetitive against rivals like Vietnam or Mexico. This impending economic shock forced New Delhi to the negotiating table, setting the stage for the February framework.

1.3 Legal Fragility: The IEEPA Controversy

The entire edifice of this new trade regime rests on the President’s broad authority under IEEPA to regulate commerce during a national emergency. This usage of IEEPA—to impose tariffs for economic rebalancing rather than strictly for sanctions against hostile actors—has sparked intense legal debate.

As of early 2026, the US Supreme Court is deliberating Learning Resources v. Trump, a consolidated case challenging the constitutionality of these tariffs. The Court of International Trade (CIT) had previously ruled that the reciprocal tariffs exceeded presidential authority, a decision affirmed in part by the Federal Circuit. However, the Supreme Court vacated the permanent injunction, allowing the tariffs to remain in force pending a final decision.

This legal precarity adds a layer of complexity to the India-US deal. The concessions granted to India—specifically the reduction of the reciprocal rate to 18%—are executive actions that could theoretically be undone if the Supreme Court strikes down the underlying IEEPA authority. Alternatively, a ruling against the administration could lead to massive refunds for importers but would strip the US executive of its primary leverage in future negotiations. For now, the "threat" of the tariffs remains the driving force behind compliance, even as the legal ground shifts beneath the policy.

Part II: Anatomy of the Deal – The US-India Interim Agreement of 2026

The "Interim Agreement" announced on February 9, 2026, is a diplomatic salvage operation designed to avert the rupture of the US-India economic relationship. It is not a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in the traditional sense, lacking the detailed chapters on intellectual property, labor standards, and dispute resolution typical of such treaties. Instead, it is a transactional framework: a "peace deal" in the trade war that swaps tariff reductions for geopolitical alignment and purchase commitments.

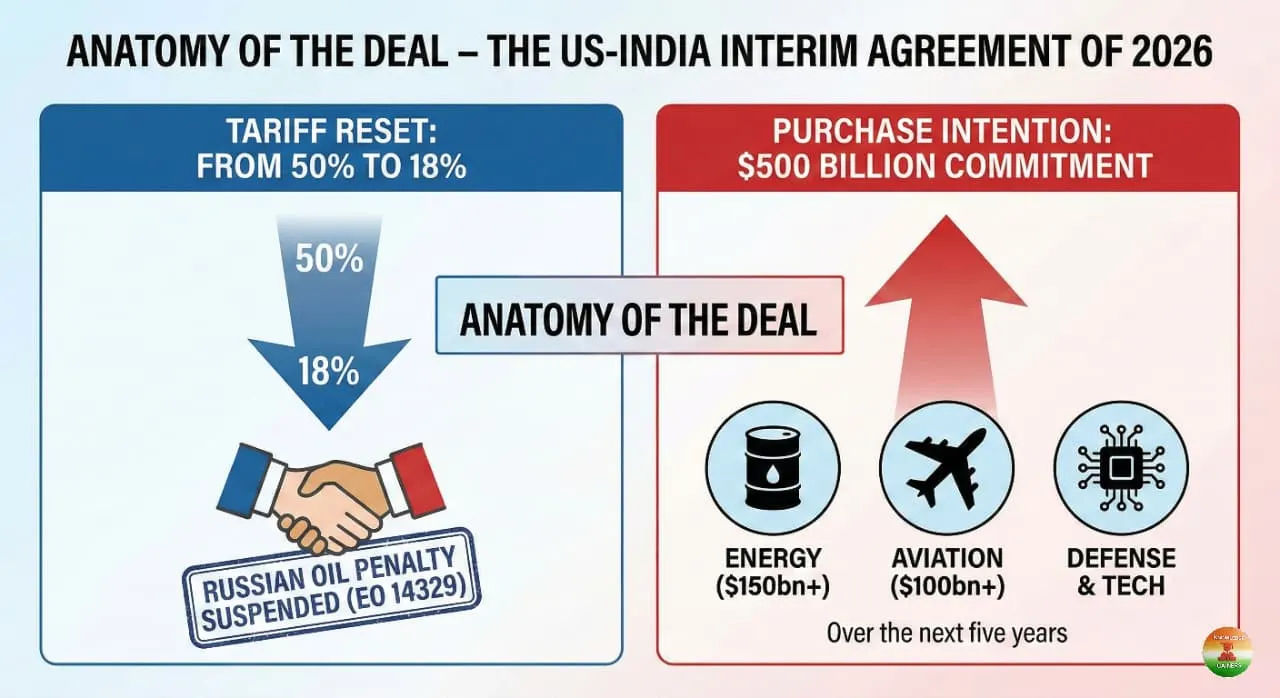

2.1 The Tariff Reset: From 50% to 18%

The headline achievement of the agreement is the dramatic reduction in the tariff wall facing Indian exporters.

Suspension of the Penalty: President Trump signed an Executive Order indefinitely suspending the 25% punitive tariff imposed under EO 14329. This removal was the direct quid pro quo for India’s commitment to halt purchases of Russian oil.

Recalibration of Reciprocity: The administration agreed to lower the "Reciprocal Tariff" rate on Indian goods to 18%.

While an 18% tariff is historically high compared to the near-zero rates under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) that India once enjoyed, in the context of 2026, it represents a significant "preference margin." With the universal baseline raising costs for all competitors, and specific adversaries like China facing rates of 34% or higher, an 18% rate effectively restores India’s relative competitiveness. The reduction applies to a broad swathe of India’s export basket, including textiles, leather, gems and jewelry, and light engineering goods.

2.2 The "Purchase Intention": A $500 Billion Commitment?

A central pillar of the US negotiating strategy was the demand for a massive reduction in the bilateral trade surplus, which stood at roughly $30-$40 billion in India’s favor prior to the deal. To address this, the framework includes a commitment regarding US exports to India.

The language regarding this commitment has been the subject of intense scrutiny and diplomatic finessing. Initial reports and draft fact sheets suggested a binding "commitment" to purchase $500 billion in US goods. However, the final public text and revised fact sheets softened this language to state that India "intends to buy more American products and purchase over $500 billion" over the next five years.

Breakdown of the Target: Achieving a $500 billion import volume over five years would require India to import approximately $100 billion annually from the US—double the pre-2025 levels of roughly $48-$50 billion. The composition of this "intention" relies heavily on three sectors:

Energy ($150bn+): The single largest component will likely be crude oil and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). By displacing Russian crude, India will need to source millions of barrels from the US Gulf Coast. US crude exports to India, which had dwindled during the era of discounted Russian oil, are expected to surge.

Aviation ($100bn+): India’s civil aviation market is the fastest-growing in the world. The deal factors in substantial orders for Boeing aircraft by Indian carriers (Air India, IndiGo, Akasa). Commerce Minister Goyal cited aviation as a sector where $100 billion in procurement is feasible given the fleet expansion plans.

Defense and Technology: The remainder comprises high-value defense platforms (drones, jet engines) and technology components, including semiconductor manufacturing equipment and specialized inputs for India’s growing electronics ecosystem.

Critics, including trade analysts and opposition politicians in India, argue that this target is unrealistic and essentially "managed trade" that distorts market principles. Even with aggressive purchases, doubling imports in a short span faces logistical and demand-side constraints. However, the "intention" language provides New Delhi with wiggle room; it is a political target rather than a legally binding quota with defined penalties for shortfalls.

2.3 The "Farmers First" Defensive Strategy

While making concessions on industrial goods, Indian negotiators maintained a rigid defensive posture regarding agriculture—the "third rail" of Indian politics. The deal reflects a "Farmers First" strategy designed to shield India’s millions of smallholder farmers from a flood of subsidized US agricultural commodities.

Exclusions: Crucially, the final agreement excluded "pulses" (lentils, chickpeas) from tariff cuts. This was a major victory for Indian negotiators, as pulses are a staple crop for dryland farmers. Dairy and meat products also remain largely protected, avoiding the political backlash that derailed previous trade talks.

Concessions: India did agree to reduce tariffs on high-value US agricultural products that do not directly compete with subsistence farming. These include tree nuts (almonds, walnuts), fresh fruits (berries, citrus), wines, and spirits. These concessions benefit Californian and Midwestern farmers—key constituencies for the US administration—while having minimal impact on India’s agrarian core.

SPS Barriers: The agreement establishes a mechanism to resolve non-tariff barriers, specifically sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) restrictions. India has committed to streamlining inspections for US pork and addressing delays in medical device approvals.

Part III: The Geopolitical Pivot – Energy and Sovereignty

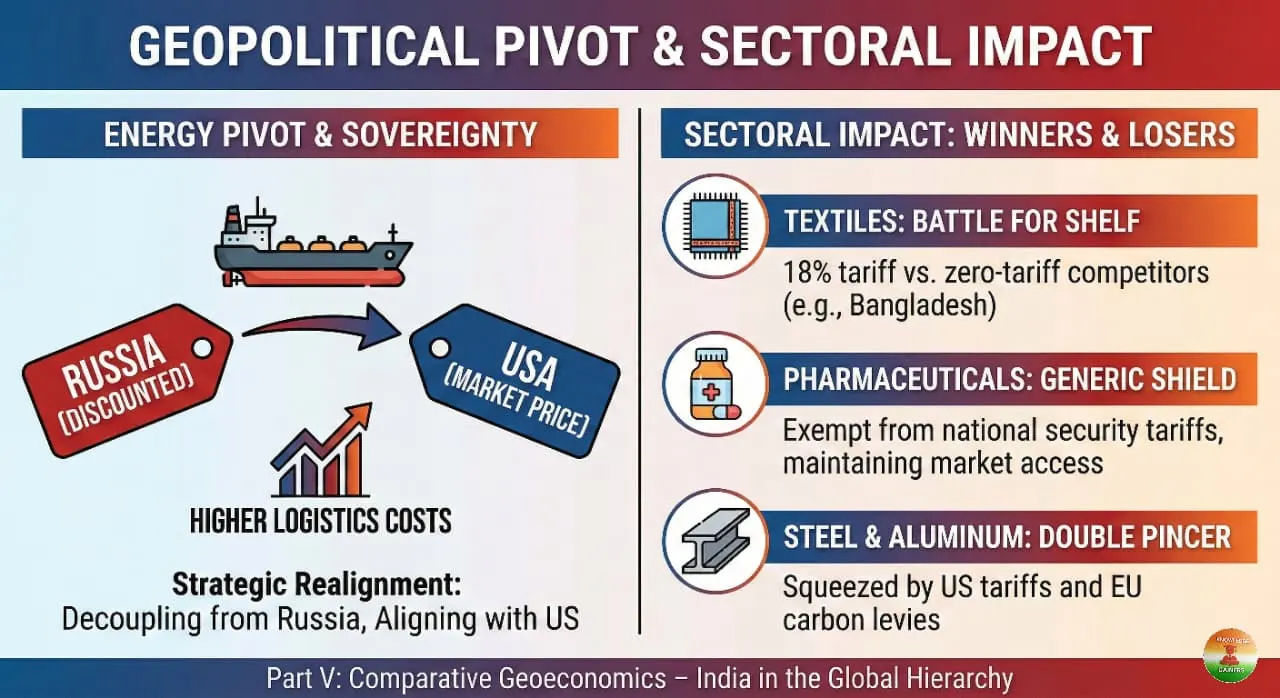

The most profound implication of the US-India deal lies not in tariffs or quotas, but in the realignment of India’s energy security architecture. The agreement forces a decoupling from Russia, ending a four-year period where New Delhi served as the economic lifeline for Moscow’s energy exports.

3.1 The End of the "Discount Era"

Since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, India had leveraged its non-aligned status to purchase Russian crude oil at significant discounts, often below the G7 price cap. At its peak, Russia accounted for nearly 40% of India’s oil imports, saving the Indian economy billions of dollars and cushioning domestic consumers from global inflation.

Executive Order 14329 ended this arbitrage. By imposing a 25% penalty tariff on all Indian exports to the US, Washington effectively taxed India’s Russian oil savings. The economic calculus shifted: the savings from discounted oil were outweighed by the potential loss of the $80+ billion US export market.

3.2 The Logistics of the Pivot

The pivot to US energy is not merely a contractual change; it is a logistical upheaval.

Crude Grades: Indian refineries, which had engaged in technical reconfiguration to process medium-sour Urals crude, must now pivot back to sweet US grades (WTI/Midland) or heavier Middle Eastern sour grades.

Shipping Dynamics: The shift alters global tanker routes. Russian oil travelled relatively short distances from the Black Sea or via the Suez Canal. US oil must travel from the Gulf Coast, around Africa or through the Suez, significantly increasing tonne-mile demand. This is expected to drive up freight rates for Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs), benefiting shipowners but increasing India’s landed cost of energy.

Inflationary Risks: Replacing discounted Russian barrels with market-priced US or Middle Eastern oil will inherently raise India’s import bill. Analysts estimate a 2-10% increase in crude costs, which could translate into higher domestic petrol and diesel prices unless the government cuts excise duties.

3.3 Strategic Autonomy vs. Strategic Alignment

The deal has sparked a fierce debate within India regarding "Strategic Autonomy." Critics argue that by bowing to US pressure on energy sourcing, India has effectively allowed Washington to dictate its foreign policy. The requirement to "stop purchasing Russian Federation oil" as a condition for tariff relief is a stark example of economic coercion.

However, proponents argue that this is a pragmatic realignment. The strategic partnership with the US—encompassing critical technology (iCET), defense cooperation, and counter-balancing China—is deemed more vital to India’s long-term rise than cheap oil from a declining power like Russia. The deal signals that New Delhi has made its choice: in a bipolar world, its economic future lies with the West, even if the terms are transactional and demanding.

Part IV: Sectoral Impact Analysis – Winners and Losers

The reduction of tariffs to 18% acts as a lifeline for India’s export-oriented sectors, but the impact is uneven. This section analyzes the specific implications for key industries, factoring in the competitive landscape and the new US trade rules.

4.1 Textiles and Apparel: The Battle for the Shelf

The textile sector is India’s second-largest employer and a critical earner of foreign exchange. Under the threatened 50% tariff regime, Indian apparel would have been decimated, ceding market share to Vietnam and Bangladesh. The reduction to 18% restores viability, but significant challenges remain.

The "Cotton Clause" Threat: A critical detail in the parallel US-Bangladesh trade deal poses a direct threat to Indian exporters. Bangladesh secured a provision allowing for zero-tariff access for garments manufactured using US-grown cotton.

Implication: This "yarn-forward" style rule incentivizes Bangladeshi mills to import US cotton, process it, and re-export it to the US duty-free. India, which relies primarily on its own domestic cotton (the world’s largest producer), will face the full 18% tariff.

Market Segmentation: This creates a bifurcation. Bangladesh may dominate the market for mass-market cotton goods (t-shirts, denim) linked to US fiber supply chains. India will likely retain competitiveness in segments using indigenous man-made fibers (MMF), silk, or high-value cotton products where the 18% duty is absorbable due to quality premiums.

Stock Market Reaction: The volatility in Indian textile stocks (e.g., Gokaldas Exports, KPR Mill) following the announcement reflects this uncertainty. The market recognizes that while 18% is better than 50%, the zero-tariff advantage for a key competitor is a structural disadvantage.

4.2 Pharmaceuticals: The Generic Shield

India supplies approximately 40% of generic drugs consumed in the United States. The 50% tariff threat raised the specter of massive drug price inflation for US consumers and shortages of essential medicines.

Section 232 Mitigation: The interim agreement includes specific "negotiated outcomes" to mitigate the impact of potential Section 232 tariffs on pharmaceuticals. This suggests that the US administration recognized the vulnerability of its own healthcare supply chain.

Outcome: Indian generic drugs will likely face the baseline 18% reciprocal tariff but will be exempted from additional national security tariffs that might be applied to other nations. This ensures continued market access for Indian pharma giants (Sun Pharma, Dr. Reddy’s) but at a higher cost base than before.

API Reliance: The deal implicitly acknowledges the US dependence on Indian Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). Any attempt to block Indian pharma would essentially shut down a large portion of the US generic drug market, a political risk the administration was unwilling to take.

4.3 Steel and Aluminum: The Double Pincer

Indian metal exporters are caught in a "double pincer" between US protectionism and European climate regulation.

US Front: While the general reciprocal rate is 18%, steel remains subject to the specific Section 232 tariffs of 25% imposed in 2018 and reaffirmed in 2025. However, the interim deal provides exemptions for specific downstream applications, such as aluminum and steel used in aircraft parts—a concession aligned with the US need to supply Boeing’s supply chain.

EU Front: Simultaneously, the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) entered its definitive payment phase in 2026. Indian steel, produced largely via coal-fired blast furnaces, has a high carbon intensity (~2.3 tons CO2/ton).

The Cost: Estimates suggest Indian steel faces a CBAM surcharge of ~€85/tonne in Europe, compared to just ~€12/tonne for Turkish steel produced via Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF).

Synthesis: With the US market protected by 18-25% tariffs and the EU market protected by carbon levies, Indian steelmakers are increasingly squeezed. This will drive a diversion of exports to price-sensitive markets in the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia, or force an acceleration of green steel investments in India.

4.4 Digital Economy and Technology

The digital services trade was a contentious area, with the US long objecting to India’s "Equalisation Levy" (a digital services tax).

Taxation: The revised fact sheets indicate that India has not explicitly agreed to remove the digital services tax immediately but has committed to negotiating "robust bilateral digital trade rules". This nuance is critical; it preserves India’s fiscal sovereignty for now while opening a pathway to a framework that prevents double taxation.

Tech Trade: The deal emphasizes increased trade in high-tech goods, specifically mentioning Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) and data center components. This aligns with India’s ambition to become an AI computing hub. The reduction of tariffs on US tech hardware (servers, routers) will lower the capital expenditure for Indian IT firms, boosting the competitiveness of India's service exports.

Part V: Comparative Geoeconomics – India in the Global Hierarchy

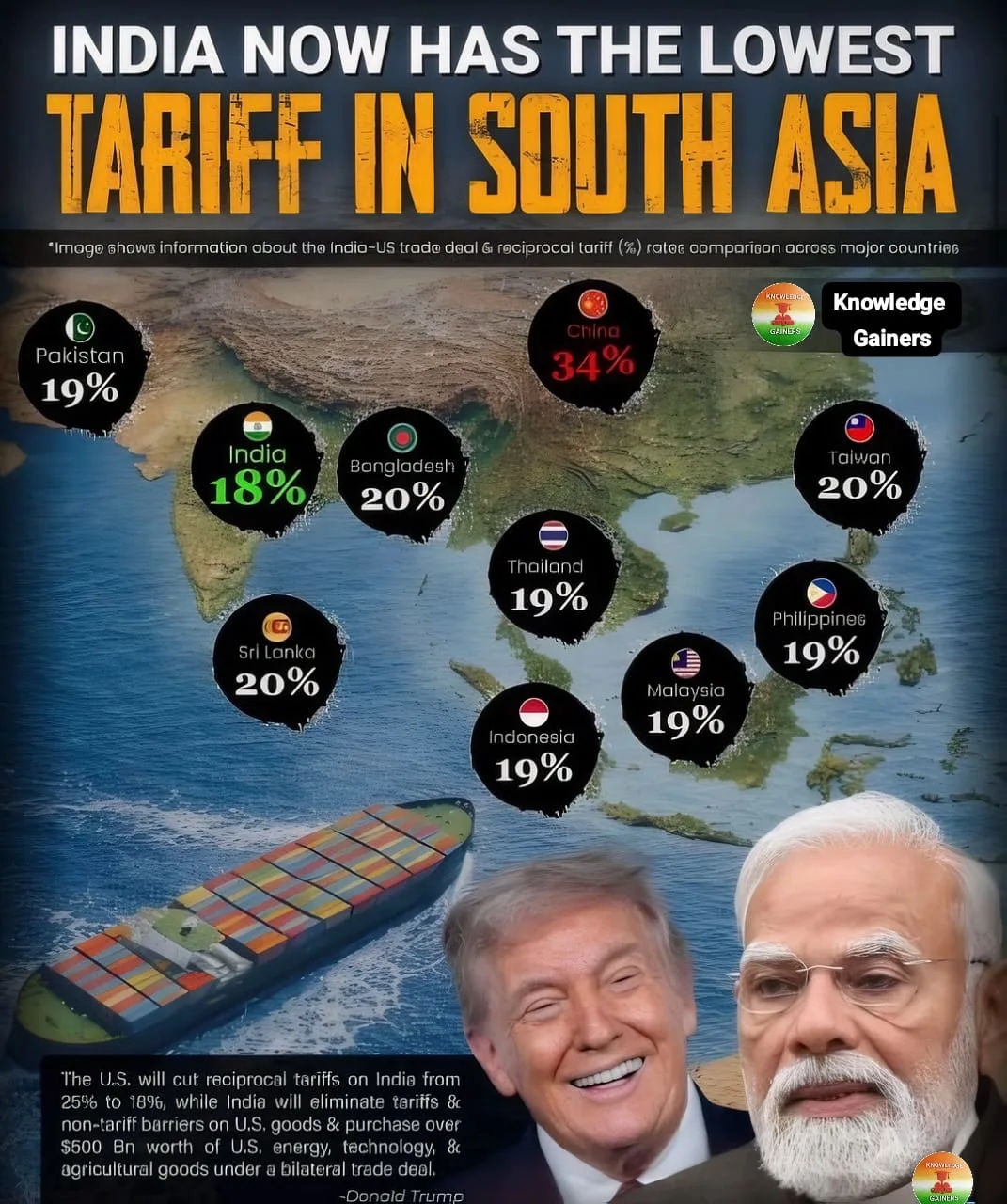

In a protectionist world, absolute tariff rates matter less than relative rates. A tariff of 18% is burdensome if competitors pay 0%, but advantageous if competitors pay 34%. The US-India deal must be evaluated against the deals struck by other major economies in the "scramble" of early 2026.

5.1 The Tariff Hierarchy

The following table synthesizes the tariff landscape for major US trading partners as of February 2026:

Country | Status | Reciprocal Rate | Strategic Context |

Argentina | Deal Signed | Cap at 10% + MFN | Political alignment (Milei-Trump); focus on food/energy. |

India | Interim Deal | 18% | Strategic counterweight to China; energy pivot required. |

Bangladesh | Deal Signed | 19% | Special 0% clause for US-cotton textiles. |

Vietnam | Negotiation | 20% | Digital trade concessions; reduced from 46% baseline. |

European Union | Framework | 15% (Floor) | Historic ally; disputes on steel/carbon remain. |

China | No Deal | 34% - 60%+ | Decoupling in effect; Section 301 + Fentanyl penalties. |

5.2 India vs. China: The Decoupling Dividend

The primary strategic benefit for India is the widening gap with China.

The Gap: With Chinese goods facing tariffs of 34% (baseline + fentanyl penalty) to 60% (Section 301), and Indian goods at 18%, India enjoys a 16-42% preference margin.

Supply Chain Shift: This margin is sufficient to drive manufacturing relocation in sectors with thin margins, such as light engineering, automotive components, and assembled electronics. For US importers, sourcing from India is now structurally cheaper than sourcing from China, even accounting for India’s infrastructure deficits.

Investment Signal: The deal signals to global MNCs that India is inside the "friend-shoring" perimeter, while China is outside. This reduction in policy uncertainty is likely to accelerate Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into Indian manufacturing.

5.3 India vs. Vietnam: The Rivalry Intensifies

Vietnam has been the primary beneficiary of the "China Plus One" strategy. The new tariff regime levels the playing field.

Tariff Parity: India (18%) now has a slight edge over Vietnam (20%). Previously, Vietnam often enjoyed better access due to more open trade policies.

Digital Trade: Vietnam’s deal requires stringent digital trade commitments and data flow liberalization. India’s deal allows for a "negotiation" on these issues, potentially giving New Delhi more time to develop its own data sovereignty framework without immediate penalties.

Outcome: The 2% tariff difference is negligible, but combined with India’s larger labor pool and the PLI schemes, it strengthens India’s case for large-scale assembly (e.g., iPhones), where scale is more achievable than in Vietnam.

5.4 India vs. Bangladesh: The Cotton War

As detailed in Section 4.1, the comparison with Bangladesh is complex. While India has a headline advantage (18% vs 19%), the sector-specific "zero-tariff" clause for Bangladesh is a strategic masterstroke by Dhaka.

Implication: India cannot compete with zero tariffs on cotton garments. To counter this, India must pivot up the value chain to MMF garments or technical textiles, or lobby for similar "yarn-forward" concessions in the final BTA.

5.5 India vs. Latin America (Argentina)

Argentina’s deal highlights the role of ideology. President Javier Milei’s alignment with the Trump administration secured a rate capped at 10% above MFN—significantly better than India’s 18%.

Lesson: Political alignment yields economic dividends in the Trump 2.0 era. While India is a strategic partner, it is not an ideological twin, and thus receives "partner" treatment rather than "ally" treatment.

Part VI: Future Outlook and Strategic Risks

The Interim Agreement is a stabilizing mechanism, but it introduces new volatilities into the Indian economy. The path forward is fraught with legal, economic, and political risks.

6.1 The "Snapback" Risk and Executive Volatility

The most significant risk is the durability of the deal. Because it is based on Executive Orders rather than a Congressional treaty, it can be revoked with the stroke of a pen.

The Russia Clause: The EO suspending the 25% penalty includes a monitoring mechanism. If the US Secretary of Commerce determines that India has resumed purchasing Russian oil, the tariffs can snap back immediately. This forces India to maintain a permanent "compliance posture," limiting its foreign policy flexibility.

Trump’s track record: The administration has a history of revisiting trade deals. The "madman theory" of negotiation suggests that threats of renewed tariffs could return if the US trade deficit with India does not narrow significantly.

6.2 The USMCA Review: The Next Flashpoint

In July 2026, the US, Canada, and Mexico will conduct a mandatory review of the USMCA. This is critical for India because many Indian companies use Mexico as a backdoor to the US market.

Rules of Origin: The US is expected to push for tighter Rules of Origin to prevent "transshipment" of components from third countries (like India and China) through Mexico.

Investment Chill: If the US imposes quotas or tariffs on Mexican imports containing non-North American content, Indian auto-component manufacturers in Mexico could see their market access curtailed.

6.3 The Long-Term Economic Transformation

If the "purchase intention" is realized, India’s economy will undergo a structural shift.

Energy Security: India will become tethered to the US energy ecosystem. While this diversifies supply, it exposes India to US Henry Hub gas prices and Atlantic basin freight rates, rather than the traditional Middle East/Russia basket.

Defense Integration: The procurement of $100bn in aviation and defense goods will deepen interoperability between the US and Indian militaries, solidifying the Quad as a de facto security alliance against China.

6.4 Conclusion: A Transactional Peace

The 2026 US-India Interim Trade Agreement is a triumph of pragmatism over idealism. Faced with an existential economic threat from a protectionist superpower, New Delhi maneuvered to secure a deal that preserves its development trajectory. The cost—higher tariffs than the past, a forced energy decoupling from Russia, and managed trade targets—is the price of admission to the American market in the mid-21st century.

For the global economy, this deal confirms the death of the old multilateral order. We have entered the age of Reciprocal Geoeconomics, where trade rates are variable, supply chains are politicized, and economic sovereignty is increasingly conditional on strategic alignment. India, by securing the 18% rate, has successfully positioned itself as a favored pole in this fragmented world, but the stability of this position depends entirely on its ability to navigate the volatile currents of Washington's executive politics.

Join our WhatsApp and Telegram Channels

Get Knowledge Gainers updates on our WhatsApp and Telegram Channels